What’s in a West Hollywood street name? Some reference land grants called “ranchos” from a period when the area was a vast coastal plain of marshes, tar pits and orchard groves. Others hint of the family histories of the men who developed the land, while one even gives a glimpse of the story-behind-the-story of a well-known Bette Davis quote.

Somehow 112 public streets have been squeezed into the city’s 1.9 square miles. A few names have multiple possible origins, others have none. As a group though, West Hollywood’s street names are a special lot and offer a local history lesson that’s hard to find anywhere else.

Just don’t expect to come across a Charlie Chaplin Avenue or Mary Pickford Street in honor of the city’s motion picture pioneers. Nearly all roads were built and named either before movie studios set up shop locally or just as “talkies” came on the scene. This also explains why stalwarts of the gay rights movement don’t show up on any street signs either.

And another thing: If you don’t like the name of your street, don’t get your hopes up about changing it. You’ll spend a lot of your own money and probably still lose. The City of West Hollywood makes it all but impossible to change a street name. Just ask the Dicks Street residents, who sought to rename their street in 2005 as Dickson Street because, well, Dickson is not a slang term for male genitalia. For a street that extends only two blocks, Dicks Street has garnered worldwide attention. On the surface, the proposed change seemed straightforward and sensible. Residents said they endured constant embarrassment whenever they had to tell anyone where they lived.

No one was able to say with certainty how or when the name came about, which appeared to eliminate any historical imperative to keep the existing name. The city council rejected the name change request anyway, given the complexity, inconvenience and lengthy process involved.

Council members then adopted a stringent policy in 2007 that requires residents seeking a street name change to pay a total of $5,000 in up-front fees. Streets can’t be named for deceased people until at least two years after they have passed away, the policy stipulates. This ensures they don’t somehow screw up their reputations from the grave. It further discourages naming streets after living persons unless substantial contributions of cash or other considerations are in play. The city’s policy notes that there has been only one name change since cityhood in 1984. That happened in 1986 when Hamel Road was changed to George Burns Road on the comedian’s 90th birthday.

A reluctance to name streets after anyone with a pulse was a big reason several members of the Los Angeles City Council struck out in 1967 when they tried to rechristen Fairfax Avenue in honor of Los Angeles Dodgers pitching great Sandy Koufax. An elbow injury had ended the future Hall of Famer’s career the year before when he was only 30 years old. But streets aren’t named for the living, explained the manager in charge of naming streets at the time for L.A.’s Bureau of Engineering.

“A person’s a hero one year, but then he vanishes from the public eye or becomes a crum-bum in the years beyond,” Harrison Kimball told the Los Angeles Times. Also, Kimball said, “It’s an embarrassing situation if the street is named for a developer and then he ends up in the clink.” Fairfax, by the way, was known as Crescent Avenue until 1913.

Edward Doheny, for whom Doheny Drive (1912) is named, flirted with going to the clink, in Kimball’s words. The oil tycoon and philanthropist was tried twice on bribery charges – and found not guilty – related to the Teapot Dome oil scandal in the 1920s. Teapot Dome ranks as the greatest and most sensational scandal in the history of American politics prior to Watergate. Doheny was richer than John D. Rockefeller at one point, but all the wealth never brought happiness. Shortly before his second bribery trial began, Doheny’s son was killed in a mysterious murder-suicide at the Doheny Mansion, or Greystone Mansion, as it is known today.

Before a name change in 1922 to Doheny Drive, the street was known as Clearwater Canon Road, according to tract maps recorded by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Works (LADPW). Clearwater Canon Road, which was dedicated in 1912, ran through the center of a neighborhood called Serenity Heights owned by Mary A. Larrabee, M.H. Hammond and J. Ross Charles.

Doheny and his second wife and widow, Carrie Estelle, (his first wife disappeared without a trace) were noted philanthropists in Los Angeles, especially regarding Catholic schools, churches and charities. Institutions that bear his name today because of his charitable contributions include the Doheny Eye Institute and the Doheny Library at the University of Southern California.

The Big Pieces of the Puzzle

Current day West Hollywood is comprised of parts of several large Mexican land grants awarded in the 1880s. That explains how four main streets got their names. The year when a street was officially dedicated is included, when known.

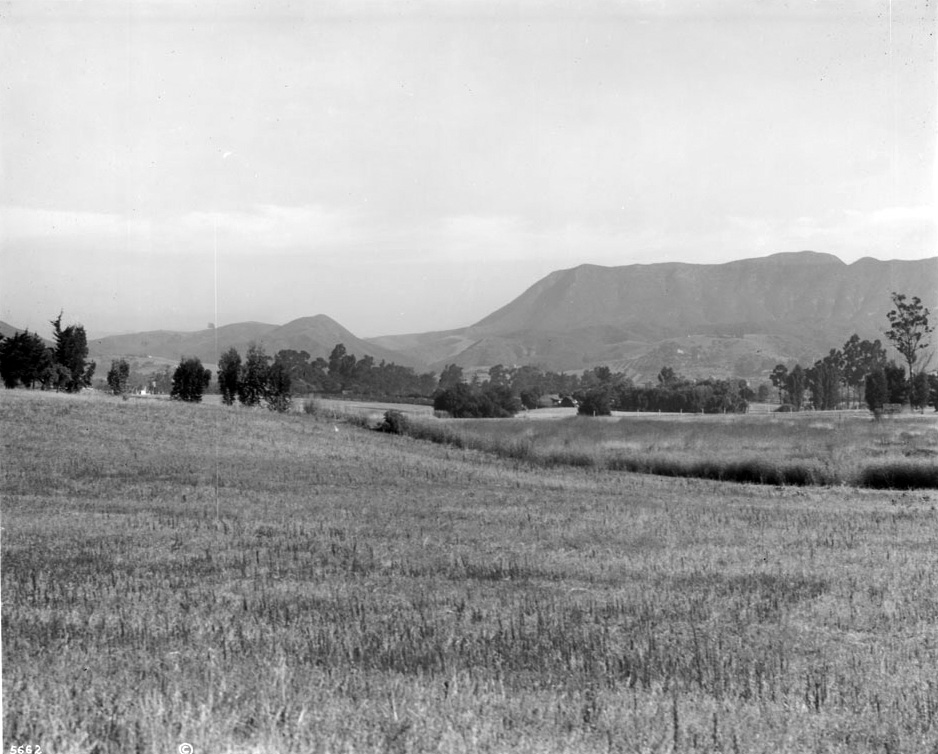

La Brea Avenue (1869): La Brea is the Spanish word for tar found in abundant supply, logically lending itself for this street’s name. Early settlers used tar for waterproofing sod roofs of adobe houses. The street was part of the 4,439-acre Rancho La Brea land grant originally awarded in 1828. The property was purchased in 1860 by Maj. Henry Hancock for $2.50 an acre.

La Cienega Boulevard (1915): This street name reflects a section of marshland along the route that was always damp and its grass was green throughout the year. “Cienega” means marshland or swamp in Spanish, adapted from Rancho Las Cienegas, a 4,439-acre rancho land grant awarded in 1823 in a low-lying area west of Los Angeles.

San Vicente Boulevard (1900): No surprises here. The street is named for the Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica, a 33,000-acre Mexican land grant given in 1839 to Francisco Sepulveda, a soldier and citizen of Los Angeles. The rancho included what are now Santa Monica, Brentwood, Mandeville Canyon and parts of West Los Angeles.

Santa Monica Boulevard (1907): An oddity about the city’s street names is that none recognizes Moses Sherman, the founder of the Sherman community that grew into the city of West Hollywood. Not that he didn’t try, of course. Sherman originally named the main road Sherman Boulevard after himself. Today, of course, it’s known as Santa Monica Boulevard. As of 1907, there was a street called Sherman Place, which may have been Moses Sherman’s fallback position since the main drag wasn’t named after him. Sherman Place is known as Shoreham Drive today.

Because Santa Monica Boulevard is the only street that links L.A.’s east side with its west side, officials agreed it was best to have a single name for the entire route. The street name is taken from the 6,656-acre Rancho Boca de Santa Monica awarded in 1839 and literally means “the road leading to Santa Monica,” according to Hollywood historian Allen Ellenberger.

National Public Radio station KPCC tells a more interesting story. It reported that Saint Monica is best known as the mother of St. Augustine, who was every mother’s worst nightmare as a teenager when he was a big rabble rouser and carouser. “Monica spent the better part of 20 years praying that her son would straighten out his life. She became the patron saint of at-risk youth.” That seems to be an appropriate name for the stretch of the street through Boystown, at least.

Agricultural / Floricultural Streets

Original roads actually followed farm and ranch tracts. Various street names reflect the kinds of crops, produce and flowers grown alongside them.

Greenacre Avenue (1912): No, it’s not a misspelling of the CBS sitcom “Green Acres” that aired in the 1960s, but it is a general description of the lush fields of produce grown in the community.

Orange Grove Avenue (1906): Obvious enough, this street gets its name from the fruit orchards grown locally.

Romaine Street (1913): The history of romaine lettuce wouldn’t seem to rate much attention in a town with all the glitz and glamour of West Hollywood. But there’s a good reason a street is named after these dark, leafy greens that are believed to help prevent cancer. Nearly all of the country’s yearly harvest today of romaine lettuce comes from California, thanks to farmers in the area that now is West Hollywood who were early adopters at the beginning of the 1900s. Over the years, it unseated iceberg lettuce as the predominate lettuce in the U.S., which once claimed 95 percent of the lettuce market. Romaine Street, by the way, originally was named Olive Avenue.

Poinsettia Place (1921) and Poinsettia Drive (1921): The enduring popularity of poinsettias in the U.S. is due largely to the gardening and marketing skills of a little-known West Hollywood family. Albert and Henrietta Ecke and their four children emigrated to the United States from Germany in 1902. They planned to stop briefly in Los Angeles before continuing their journey to Fiji.

They landed first in Eagle Rock and then moved to the Sherman community. They began growing fields of poinsettias on Harper Avenue just south of Sunset Boulevard in 1906. The sight of the red poinsettia fields began drawing busloads of tourists. A road through Ecke’s field became Poinsettia Place. Today, it extends from West Hollywood south to Hollywood and Park La Brea.

Ecke also experimented with potted plants, shipping them east from his packing house on Sunset Boulevard. The packing house later became the Westside Market; today, it’s the Roxy Theatre on the Sunset Strip. After his death, his son Paul began cultivating in earnest, trying to perfect the first poinsettia that could be successfully grown as an indoor plant. He promoted it worldwide and helped found the American Florists’ Exchange, across the street from the downtown Los Angeles flower mart.

The Name Game

Naming streets wasn’t always the buttoned-down process that it is today. When the community of Sherman wasn’t much more than a lawless outpost in the hinterlands between Los Angeles and the beach cities, flexibility was the name of the game. Handwritten notes on tract maps recorded with Los Angeles County’s Public Works Department are the only official record of many such changes.

The 1907 tract map for Sherman Heights, for example, established the Clark Street name (in honor of Moses Sherman’s brother-in-law and business partner Eli P. Clark). Ozeta Terrace originally was named Hill Street, while Shoreham Drive initially was called Sherman Place. Notes added to the 1907 map for the A.A. Barnett Tract (essentially Hancock Avenue) recorded the transition from Sherman Avenue to Santa Monica Boulevard.

Also in 1907, the former Conklin Street and Whipple Avenue were combined into a single street that today carries the name of Hilldale Avenue. The McNair Place tract was a very large neighborhood bounded on the east by Fairfax Avenue and on the west by Gardner Avenue. Notes on its 1913 tract map established the new street name of Willoughby Avenue and changed the name of Olive Avenue to Romaine Street. It also recast the former Friend Avenue as Ogden Drive, while changing Fulton Avenue to Spaulding Avenue.

# # #

Sunset Strip historian Jon Ponder contributed to this article.

Originally published in WEHOville.com.

This is the second of two stories exploring the history underlying the names of various streets in West Hollywood. The first was published July 5. The year when each street was dedicated is indicated after the name. Such information is on file at Los Angeles County’s Public Works Department, because all city thoroughfares were named when the Sherman / West Hollywood community was under county jurisdiction.

The Sunset Strip isn’t an official street name, but it is West Hollywood’s most identifiable asset. Businesses along the curvy section of Sunset Boulevard that cater to the music, comedy, celebrity and glamour crowds generate worldwide publicity and a hefty portion of the city’s annual tax revenues.

How many people realize that residents preferred another nickname for The Strip when a contest was held in 1937? They chose “The Sunset Eighties,” a reference to the 8000-numbered blocks that comprise the meandering stretch of Sunset Boulevard through West Hollywood.

Sponsored by the Hollywood Citizen-News daily newspaper, the contest paid the winner $25 for his submission. “It tells people where we are – and it’s catchy,” an executive with the Chateau Marmont hotel told the newspaper. The contest, by the way, was held in 1937 to mark the first time the entire length of Sunset Boulevard was paved, notes Sunset Strip historian Jon Ponder. County crews doing the roadwork simply called the street “the county strip,” and the name “Sunset Strip” stuck instead of the winning contest entry.

City officials ever since have zealously guarded the nickname, seeking to make sure it is closely identified with West Hollywood. A 2004 story in The New York Times about the landmark Argyle Hotel along the Strip carried a “Hollywood” dateline, sending the Convention and Visitors Bureau into a protectionist dither.

The bureau launched a campaign over which clubs and eateries along Sunset Boulevard could rightfully claim they were on the Sunset Strip and had the right to use the nickname. Brad Burlingame, the late head of the bureau, said the name should not be applied to the stretch of Sunset Boulevard that extends east of their city into neighboring Hollywood.

Burlingame claimed to be merely protecting the city’s most identifiable asset by taking steps to prevent Los Angeles from hijacking the Sunset Strip’s aura. “A city as big as Los Angeles is confusing to everyone, and West Hollywood’s borders are very difficult to understand,” Burlingame told the Los Angeles Times.

The bureau hung 120 banners from streetlights along the city’s 1.7 mile section of Sunset Boulevard that proclaimed “Sunset Strip – Only in West Hollywood.”

The rest of Sunset Boulevard has a notable history too. The street existed as early as 1780 as the major connecting road for El Pueblo de Los Angeles and all ranches westward to the Pacific Ocean. It originally was called Bellevue Street, with small sections named Short, Bread and Marchessault streets (after L.A.’s seventh mayor, Dennis Marchessault).

Sunset began on the hilltop estate of Cornelius Cole in Hollywood, which had a great view of the sunset over the Pacific Ocean. From there, it’s simple to extrapolate how the street got its name. Cole was a U.S. congressman and senator who originally organized the California branch of the Republican party in 1856.

Streets Named by Land Owners and Developers

The importance of Canadian native William Hamilton Hay to West Hollywood’s development cannot be overstated, historians believe. Hay alone built the luxury estate that Russian actress Alla Nazimova purchased and turned into the legendary Garden of Alla Hotel. Hay also developed a 160-acre neighborhood to the east of the hotel that he called Crescent Heights, thus giving rise to the name of the street alongside it, Crescent Heights Boulevard (1905). The same year, Havenhurst Drive was named with the “y” intentionally dropped from Hay’s last name, according to county land records. Another street named after Hay – Hay Avenue – was changed to Hayworth Avenue in 1905 as well. Finally, Norton Avenue (1910) was named for C. E. Norton, Hay’s partner in a Los Angeles real estate practice.

Hancock Avenue (1907) is a salute to Major Henry Hancock, who acquired about two-thirds of the immense Rancho La Brea land grant in 1870 through his brother John. He was a New Hampshire native, Harvard-trained lawyer and government surveyor who came to California during the Gold Rush. There were constant battles over who actually owned the land, and it was not until 1877, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Hancocks, that the disputes were settled.

John Hancock was formally granted 1,200 acres, and Henry ended up with 2,400 acres. Other men were given small portions of the Rancho. Hancock Park, by the way, was developed by Henry Hancock’s son.

Hancock retained a future U.S. senator, Cornelius Cole, to represent him in court battles over the land titles. To pay Cole for his services, Hancock deeded an undivided one-tenth interest of Rancho La Brea to Cole.

This unloosed a plethora of street names around town, according to historian Allen Ellenberger. Olive Drive (1910) belongs in this group – and not in agricultural produce – as it’s named after Cole’s wife, Olive

.

Waring Avenue (1914) takes its name from Cole’s son-in-law, Capt. Howard Waring. Willoughby Avenue (1913) is named for Cole’s son Willoughby. As a sidelight, 11 streets in and around modern-day Hollywood were named after Cole family members.

Gardner Street (1910) originated with Dr. Alan Gardner, an investor and partner of banker Rollin B. Lane, who built the Magic Castle. Gardner owned tracts of land in the Hollywood area and in the San Fernando Valley.

The Hollywood home of French painter Paul De Longpre, a close friend of Cole’s, became a world famous tourist attraction. A street named in his honor was all too logical, so today there’s De Longpre Avenue (1913).

Beverly Boulevard (1921) is one of two city streets with a Massachusetts influence. It’s named for Beverly Farms, Mass., a favorite vacation spot of President William Howard Taft. The founder of Beverly Hills, Burton Green, figured that naming the street after Beverly Farms would be a good way to lure people to his city. In 1906, Burton named a street after himself – you guessed it, Burton Way.

Melrose Avenue (1887) is the second Massachusetts-influenced thoroughfare. Ranch owner E.A. McCarthy named the route after his hometown of Melrose, Mass.

Naming streets for developers seems to have been sacrosanct and fiercely defended by city officials, as the naming of Robertson Boulevard in 1923 showed. The City of Los Angeles agreed to rename its section of Preuss Road as Robertson Boulevard to honor developer George Robertson. Beverly Hills also voted to rename its stretch of road after Robertson. But according to the Los Angeles Times, Culver City balked: Harry Culver, the city’s founder, refused to allow the name of a competing developer to adorn a street in his town. The Robertson Boulevard name stops at Washington Boulevard – just inside the Culver City border.

Mysteries of the Norma Triangle

Streets in the Norma Triangle neighborhood seem at times to be something of a Bermuda Triangle of street names. Their lineage has existed for many years in the murky realm of local legend rather than in historical fact. And then there’s the disputed lineage of four streets in the west side’s Norma Triangle neighborhood – Norma Place (1922), Lloyd Place (1922), Cynthia Street (1922) and the ever-popular Dicks Street (1922).

Local legend has it that silent film star Norma Talmadge had a film studio in this neighborhood. Surrounding homes supposedly were stars’ dressing rooms, with remaining streets allegedly named for them. That theory has been pretty much put to rest, though, by historians who couldn’t establish any connection between Talmadge and the neighborhood. They believe the streets actually were named after senior executives of the Los Angeles Pacific Railroad Company, owned by Moses Sherman and Eli P. Clark, who built the streets, or their spouses or children. There’s historical evidence to support the theory, according to the Electric Railway Historical Association, whose records show the following:

• Clark Street (1907) is named for Eli P. Clark, Sherman’s brother-in-law and business partner.

• Hammond Drive (1907) most likely carries the name of M.E. Hammond, treasurer of Sherman’s Los Angeles Pacific Railroad.

• Larrabee Street (1906) apparently is named for W.D. Larrabee, superintendent of the Los Angeles & Santa Monica Electric Railway, one of many railways owned by Sherman.

• Sherwood Drive is believed to be named for Robert Sherwood from the Los Angeles Railway.

• Croft Avenue perhaps carries the name of Joe Croft, a senior manager of conductors / motormen for at least one of Sherman’s streetcar lines.

Not every street fits nicely into any particular category. One of the most charming neighborhoods anywhere is Spaulding Square, eight square blocks of beautifully restored homes in Colonial Revival, Craftsman, English Revival/Tudor, Italian/Mediterranean Revival, Prairie and Spanish Revival styles. The neighborhood and Spaulding Avenue (1913) are named after Alfred Starr Spaulding, its architect. Fulton changed to Spaulding and Spaulding changed to Stanley.

St. Thomas the Apostle Episcopal Church on Hollywood Boulevard traces its beginning to pioneer Mary G. Ogden, who organized a church school in her West Hollywood home in 1919. Ten people attended the first service, and Ogden Drive is named in her honor. Ogden originally was named Friend Avenue.

The story about how Fountain Avenue (1905) got its name is not clear based on county land tract maps, but many believe it has something to do with the incredible concentration of turreted French Norman and other period revival style apartment houses built around large, garden courtyards with elaborate fountains. The street is also known as “Fountain Freeway” because it’s a much faster alternative to Santa Monica Boulevard – a story enforced by Bette Davis herself. During an appearance on “The Tonight Show,” host Johnny Carson asked her advice on the best way for an aspiring starlet could get into Hollywood. Ms. Davis replied without hesitation, “Take Fountain!”

The Name Game

Those with money or political power certainly liked to play around with street names in the early days. Official Los Angeles County tract maps show these significant changes:

• There was a Plummer Street along the eastern-most boundary of today’s city limits – no doubt named for Col. Eugenio Plummer, who acquired 160 acres of land in 1874 where Plummer Park is located today. Plummer Street existed until 1906, when its name was changed to La Brea Avenue.

• Another big change recorded on county tract maps states that the former Newcomb Street underwent a name change to La Cienega Boulevard in 1910.

• Before Lexington Avenue was given that name the same year, it was known as Emelita Avenue. Also in 1910, a portion of Alfred Street was changed to Hacienda Place.

• The first article posted July 5 notes that Friend Avenue was renamed to Ogden Drive in 1913. It turns out that Friend was previously known as Mountain View Avenue until 1906.

• Present-day Edinburgh Avenue also had a previous life – as Donald Avenue – until it got its current name in 1920.

###

Sunset Strip historian Jon Ponder contributed to this article.